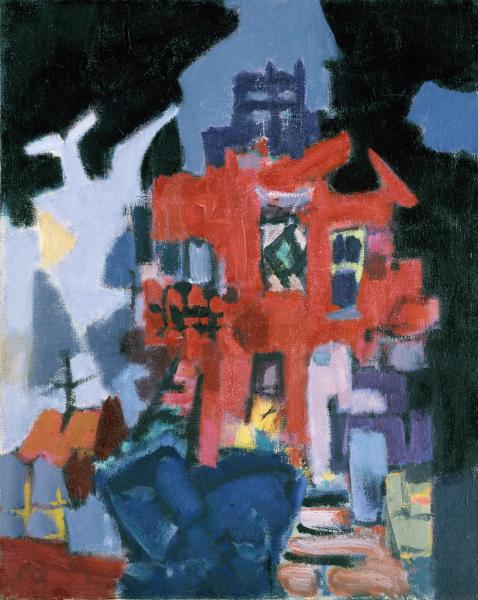

Jacob Kainen, House with Black Sky, 1949, oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Mrs. Betty B. Ross, 1979.81.

Sealed

by Miko Ann

The apartment is big: two floors and a rooftop with views of the Bronx. It’s meant for more than two people. The dog and cat sniff corners for missing family members. My brother Seth could be sleeping on someone’s roof, but he could also sway through our door any moment, expecting to eat dinner with us. Dad is at the treatment center on Nineteenth Street. Mom says they will help Dad with his addictions. Maybe they can cure him so he won’t want drugs more than us.

Chocolate, Seth’s pit bull, rests his chin on my knee, his eyes asking where my brother is. I stroke Chocolate’s snout where scabbed flesh wrinkles beneath his whiskers. His body is marked with wounds earned in fights my brother forced him into. I examine the pit bull’s scars like maps, seeing where they lead. Pink skin hardens in a deep scratch on the side of his neck. Once, he came home with the pads of his feet cracked open, a trail of bloody paw prints on the dining room floor. I take a paw and feel the rough cushion, now healed, stronger. The cat leaps onto the couch and curls up next to me. He doesn’t want to be left out.

Dad’s box sits in front of us partially opened. Only one box left behind. He’s supposed to have moved out for the last time, but I hope he will be back. I’m not sure if he is allowed back here. If he’s gone for good, will Mom meet him somewhere and give him the box or throw the box away? My thoughts make circles, the same questions without answers.

Dad sends me letters from the center, tells me he’s praying. I’ve tried to pray a few times, but in the nine years I’ve been alive God’s never spoken to me. I can’t talk to someone without knowing they’re listening. Sometimes I say, Make Dad better, so that he and Mom can be in the same room together. Then the empty spaces can start to fill up.

There are other families similar to ours, same problems. I see them on the news at night, and it never ends well. A picture of them together, a nice one to send out for holidays, flashes on the screen. The news person says, They seemed like the perfect family, but horror lurked behind closed doors. A member of the family breaks, the news reports the happening to the rest of the neighborhood. In my dreams, Seth comes back home, and he kills Mom and me. Sometimes Dad kills him. That’s how it goes on the news. If I dream about it enough maybe it can turn out differently for us.

I think Seth is still close to our apartment in Inwood. Mom calls his friends all the time to make sure he’s okay, but sometimes days go by with no word. Maybe Seth would know what to do with the box. He probably wouldn’t care. Seth and Dad don’t speak to each other anymore. Seth’s room still has a big hole he punched into the wall. The last time I saw him in there, he was trying to get out of Dad’s grip around his neck and face. I was frozen in the doorway, and Seth was yelling with his mouth closed.

I stand in front of my open closet, holding Dad’s box to my chest. The animals followed me from the couch, and they are waiting for me to make a decision. What if Dad forgets about his box? Then it will be thrown out, and he will be completely erased from our family’s apartment. If Dad asks for the box and my mom can’t find it, he will have to come back to the apartment to search for it.

I put the box on my shelf and shut the door.

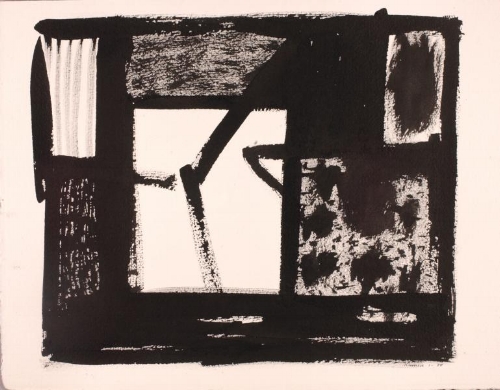

Jacob Kainen, Sanctum, 1980, brush and ink on paper, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Christopher and Alexandra Middendorf, 1991.7.4.

School is crowded, metal lockers slamming and voices losing their identities inside one another. The lunchroom smells like old hamburger meat, but I have my lunch from home in a tied up plastic bag. PB+J, Polly-O string cheese, and a juice box. Once, I opened my lunch and found a butter sandwich. Dad must have made it. Today I sit at one of the long, white tables, open the two pieces of Wonder bread, and pretend the jelly is an oozy slice of tomato like in Harriet the Spy. Harriet always eats tomato and mayonnaise sandwiches, and I want to be like Harriet. I know what I like, and I know—I slam the slices back together—that I like—and smash it flat with my fist—tomato. I actually hate tomato and mayonnaise, but it’s fun to pretend.

My best friend, Elsa, and I live through Harriet’s adventures. Our bendable composition notebooks say PRIVATE on the front, daring anyone to read. No one can know the secrets of a spy. I don’t have much written down though. It’s hard to keep a journal like Harriet. There’s usually nothing interesting to write about, so we have to look for people to spy on, picking different places to hide in and observe.

After lunch, the playground turns into Harriet’s neighborhood. Cushioned ground becomes the dirt paths that lead to the wind chime garden. Our jungle gym turns into tall trees with tin cans hanging from the branches. Elsa and I look through kaleidoscopes underneath what used to be the slide but is now the iron gate to the garden, as tall as the trees. I draw an Animikii, the thunder spirit, with a purple marker on the bottom of my foot. The Animikii is a symbol for friendship in the movie. Elsa presses her foot against mine. A secret tattoo is so much less painful, and now we’re blood buddies, like Harriet and her friends.

The Y picks Elsa and me up after school, so our moms can keep working. It’s better than being in the empty apartment, Dad’s box sitting alone in my closet. Sometimes the Y takes us to Discovery Zone, the best place on earth. The plastic tube slides lead to spindly tubes that roll your body through to the monkey bars, all contained in a netted box. You climb and crawl from room to room, never knowing where you’ll end up. Elsa and I usually stake out this netted bridge with the other girls and attack the boys if they try to pass through our territory. Same for us if we go to theirs. Babies and kids outside the Y group don’t count. Our fighting is family only.

We pull into the parking lot, the big, yellow letters getting closer: DISCOVERY ZONE. The counselors yell over us, make us buddy up as we cross the lot. Elsa and I are in the back since we’re the oldest.

My reversible jacket is heavy on my shoulders, and I decide I should have left it behind. I run back to the bus alone to put it on my seat. The counselors are opening the Discovery Zone door, their backs to us, when I break away. Jacket off, I’m jumping from the school bus steps as the last kid’s head disappears through the doorway. I hear their voices fade as they enter DZ. I don’t hear the wheels of the white SUV coming toward me. I don’t see it when I emerge from between two parked cars. I only see the light reflecting off the big, yellow letters.

This boxy vehicle and I are like two perpendicular lines drawn on a sheet of graph paper, destined to meet at a certain point. I don’t feel the impact against my right hip, the lightness of my body in midair, the back of my head smacking concrete, the crunch of my right collarbone. I don’t see the mom behind the wheel or her kids in the back seat. All I see is the yellow light.

The clouds are threatening rain, and thunder claps overhead. Faces and hands come into view, touching me, reaching over me, then fading. A whiff of tar before something plastic is placed over my nose. The voices are getting lost, too many people talking at once like at school. I think they’re talking to me, giving me instructions. Everything feels too heavy to focus, like that moment right before you fall asleep.

My eyes close and open again. Mom is in the chair next to my hospital bed, leaning over with a serious face behind her glasses. Her outfit is different, so I know I’ve been here a few days.

You didn’t even remember your name, she tells me. It was very scary. She looks like she’s going to cry, but she opens a juice box for me instead. I push it away because it makes me want to puke, and I’m not done asking questions. I want to know everything. I want to remember not remembering.

The next time I wake up, Dad’s face comes into focus. Hey, Baby Girl, he says. He kisses my forehead, and his smell makes me feel like I’m home. I hope Mom doesn’t come in the room.

There’s a groaning in my stomach.

Can I have some Froot Loops?

Dad smiles as if my ask for cereal is the most exciting thing in the world and leaps out of his chair to get a nurse.

Seth is sitting in a chair in the corner beneath the TV. His hands are together and his head is down, but his eyes are looking at me. I was starting to forget what he looks like. It is right that he’s here. It’s like when you see the weirder-looking puzzle piece and think, There’s no way it will fit in, but it does. It lines up perfectly and the puzzle starts looking like a picture.

But this picture isn’t what I was hoping for when I hid Dad’s box. We’re not in Inwood. I’m in a white bed with metal bars, my right leg propped up in a cast that wraps around my broken hip. My right arm rests in a sling, supporting my broken collarbone. Half of my body is useless. There are tubes stuck up my nose, and I have to fight the urge to rip the needle out of my hand. I stare at the wall, swirling in the white until I’m upside down.

I could have died. The machine beside my bed beeps in agreement. I sink into my covers, letting them swallow me up. I hear a newscaster’s voice, The nine-year-old girl was struck and killed by an oncoming SUV. I eat my cereal, crying into the Styrofoam bowl. Mom comes into the room even though Dad is there. We’re all here together, but it’s still quiet, a filled up space that somehow feels empty. My parents can’t be like Elsa’s, who get along even though they’re not together. My big brother can’t always be home like hers is. There is no family blueprint, no way to look ahead and see what is in store for all of us next. My mom and dad and Seth come together around me, and it is like the room has expanded to infinity and then shrunken back tight. In a week I will go home and my dad and brother won’t be there because nothing is permanent. The Animikii I pressed onto Elsa’s foot must have washed off by now. I shovel spoonfuls of Froot Loops into my mouth, and I am the only one crying.

My leg is wrapped in hard plaster for two months. When I am home alone, I wheel myself to my room, open my closet, and find the shelf where Dad’s box was sitting is bare. Did Dad come home while I was in the hospital to get the box? I decide not to ask Mom if I missed him. It doesn’t matter. Harriet the Spy would never say it doesn’t matter. But what Harriet doesn’t understand is that my dad belongs at the treatment center. Seth belongs on a roof not too far away. We are all recovering together, apart.

The cat watches me from his spot on the armchair, and Chocolate walks over to where I’m lying on the couch, puts his chin on my shoulder. His eyes are like liquid marbles, brown to match his fur. He starts moving himself along the couch, toward my legs, snout up and sniffing at the cast. When it comes off, I’ll press my right foot against his paw so our friendship can be sealed. He sees straight through the thick shell to the place where my leg was opened up and closed, following my scars to see where they lead.

Published December 9th, 2018

Miko Ann is an astrological, techno yogi who writes about her experiences, and sometimes fiction too! She holds a BA in Creative Writing from New York University and her work has appeared on the online magazine, Mr. Beller’s Neighborhood and Deviation.

Jacob Kainen moved to New York at a young age and began studying drawing at the Art Students League, the Pratt Institute School of Art, and the New York University School of Architecture. In the 1930s, he began his career as a social realist painter because of his strong interest in conveying the human experience. He later abandoned this style in favor of abstract expressionism, and became friends with fellow painter Arshile Gorky. In 1942, Kainen joined the Smithsonian as an aide with the Division of Graphic Arts at the U.S. National Museum (now the National Museum of American History) and by 1946 was appointed curator. Later, in 1966, he served as a curator of graphic arts at the Smithsonian's National Collection of Fine Arts (now the American Art Museum), where he expanded the collection of modern American prints and drawings. Until his retirement from the Smithsonian in 1970, Kainen spent his days researching at the Museum and dedicated his evenings to studio work.