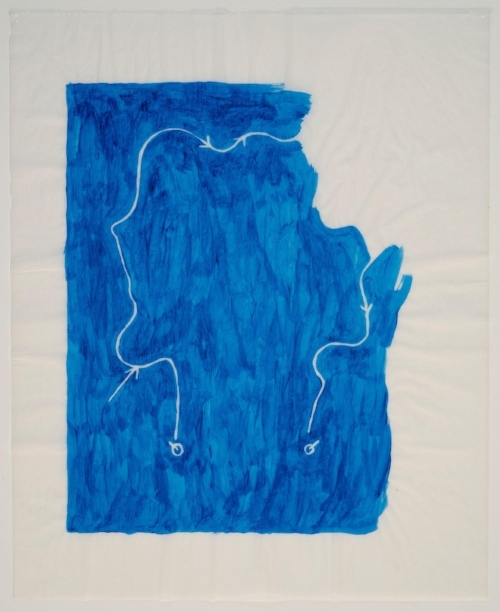

Elena Dao Jing Yu.. From Notation Score Paintings, 2015, series of twelve paintings, 17" x 14", acrylic on tracing paper. Photograph courtesy of the artist.

Overwintering

by Lucy Jones

If I stood up and looked out of the slanting windows of our living room, I would be able to see the Black Forest mountains, distant and craggy against the grey skies. But right now, I’m sitting on the red sofa, staring into the baby’s room at the changing table I struggled to put together a few days ago. Now I’m thinking how I will have to take it apart. I feel the urge to stand on that exact spot where I assembled the pieces: Perhaps a gap will open up and I’ll slide through it back to the past. Once there, I will make things turn out differently.

The physical urge to move is so strong that I stand up. My husband looks at me in surprise, and the undertaker sticks a finger into his collar and wiggles it around. His business has five stars on Yelp. That’s how we decide things these days—just follow the signs. There is so much bureaucracy to wade through. I look from my husband to the undertaker and realize they have been discussing a question to which I am now expected to provide an answer.

The air in our attic flat is stuffy, despite it being mid-September, and sweat is beading on my husband’s hairless scalp. He smells different these days. He has a listless air, punctuated by periods of uncontrollable restlessness. At mealtimes, we try to avoid sitting at the table too long after dinner. We pick at our food. Drink instead. Crates of red wine ordered online appear on the doorstep, lugged up the six flights of stairs by our DHL guy. Some of the bottles cost €40 each. There is a perverse satisfaction in consuming wine we can’t afford that does our health no good. We grimly apply ourselves to the task.

One night, I get up to fetch myself a glass of water from the kitchen. As I open the door to the moonlit living room and am about to walk through, I can make out my husband on the red sofa. There’s a scratching sound. It takes a moment before I realise it’s his fingernails, working the edge of one of the cushions. I squint, he stares back, his eyes swollen from crying. Nothing comforting comes to mind to say. I think I should go over and hug him. That’s what a normal person in this situation would do. But I'm afraid that his mourning will add to mine and gather strength, making things worse. We can only keep going if we don’t cross the divide. If one of us slips into sympathy for the other one, the heartbreak will engulf us completely.

There’s a name for what we’re feeling—“empty arms syndrome.” I wish I had something more concrete to show for it, like plaster casts. Something that people, even strangers in street, could point to. Perhaps they’d ask, What happened? and I could say, I hurt myself. They might invite me for a cup of tea, say comforting things. When I hug my husband’s big body, the void only increases. Two sets of empty arms make four.

Each phone call is a minefield. Everyone has a story to tell. Everyone wants to join the horror show, tell us their worst experiences. I am immobilized by the mounting pile of tragedies I have to hear every day. But I can’t tell them to stop: I just don’t have the energy. I envy my husband his work. He has a purpose and a place to go where everyone is briefed, everyone knows, where his attention gets diverted; but it has become my full-time job to listen to the tragic stories people tell me. The phone calls are marginally better than meeting people I haven’t seen since it happened. They bound over to me in supermarket aisles and say expectant things like, We-e-e-ell…? My words are monotone and rehearsed: their expressions invariably cloud. I watch small inner struggles take place. They often cry. I stand rigid, not able to give into another wave of grief: not in the grocery store, for God’s sake.

I want these chance meetings to stop and so, one afternoon, with a resolve that surprises me, I go to the places I have frequented over the past nine months, and I tell them what has happened. Some don’t even need me to say anything. They see my pale face, my lack of belly, no pram, and guess correctly. The Italian delicatessen owner hurriedly makes the sign of the cross. The woman who sells handmade stuffed toys squeezes my hand. Two women in the park that I am on nodding terms with back away with their strollers. The bicycle-shop owner gives me a free tool bag. Afterwards, I feel purged. Or at least less like a driver hurtling the wrong way down the motorway, staring at the terrified faces of people in their cars as I pass.

I am still standing, staring at the changing table, and so I sit back down on the red sofa and ask, “What was the question again?”

The undertaker shifts in his seat.

“You mentioned on the phone that you want to take your son to Berlin with you when you move,” he says.

My husband’s fingers are on his temples, massaging them slowly.

The undertaker takes a file out of his briefcase and opens it. He consults some kind of list.

“We’ll dig a shallow grave for the funeral next week. That way we can dig the body back up again and transfer him when you’re ready.”

I look at my husband, who is now contemplating the undertaker with a puzzled, startled expression. “And… how will he be brought to Berlin?” he asks.

The undertaker shifts conspiratorially forward until he’s perched on the very edge of his seat. He pushes his spectacles up on the bridge of his nose and looks around, as if to see if anyone else is listening.

“Well, here’s the thing,” he almost whispers. “We can either drive the body in our hearse—that would be the usual way to do it. And then it’ll cost you this much,”—here, he turns the clipboard around on his lap and circles a sum with his biro. “Or you could drive him yourselves, which strictly speaking is illegal, but then it would only cost you this much.” The tip of his pen quivers, resting on the second figure.

“I have a cousin who works at the cemetery in Berlin,” he adds, by way of explanation.

My spirits sink a notch lower. The difference in price is devastating: around four months’ salary. And we’ve already drunk away most of this month’s budget. But the idea of driving to Berlin with our son’s body in the car boot is equally devastating.

“My son would have been thirty-two this year,” the undertaker says with trained empathy, leaning back for a moment.

Here we go, I think.

“My wife had a placental abruption at the traffic light on the way to the hospital,” he says, a sentence I know he has repeated many times. “Our son opened his eyes for a few moments, but then died in her arms.”

They saw the colour of their son’s eyes, I think. We don’t know what colour our son’s were. He was born with them closed. Born sleeping, as they call it on the forums.

Elena Dao Jing Yu. From Notation Score Paintings, 2015, series of twelve paintings, 17" x 14", acrylic on tracing paper.

Six months later. We’re in a cold snap. We are muffled in woollies as we clamber into our old Volvo outside the flat, its suspension sinking under our weight. The cold weather is not the only reason we’re freezing: we can’t switch on the car radiator tonight.

No one is out on the street, and the fog makes haloes around the streetlights. The drive from our flat is familiar, even though everything looks different at night: the privet hedges are grey, bolstered by chest-high sandstone walls. We turn onto the ring road, past the 1970s high-rises and on toward the palatial entrance of the cemetery. The ochre facade is imposing in the light from the car’s headlights. We park in a side street and get out, stamping our feet and blowing into our hands. A change in weather to suit the occasion. Most leaves are dangling limply from the plane trees, reddish and yellow and zigzagged at the edges, caught unawares by the sudden frost.

The undertaker appears at the cemetery office door and signals for us to come over. We are ushered into a tiny room, lit by a desolate neon strip. On the desk is a small package: our son’s coffin, made of pale wood and wrapped in a cheap white blanket. Months ago, I carried it to the shallow grave. We held hands and said words and watched as he was lowered into the earth, only to be dug up again tonight like a dahlia bulb before the winter.

“Now remember: no stopping. Have you got a full tank?” the undertaker checks.

We nod solemnly.

“If you need my help, just call.”

He places the light bundle into my husband’s outstretched arms and pats us both lightly on the shoulders.

“My cousin will be there to meet you at 6 o’clock tomorrow morning,” he says, remaining in the neon-lit doorway at a respectful distance.

We push aside the inline skates and camping gear, the big plastic bag of beach things and spark plugs, and tenderly place the bundle in the middle of the car boot. We straighten up, both looking at how we’ve arranged our son, me with my hands on my hips.

“Hold on a minute,” I say, and start taking everything out of the rear of the car except the white bundle. I can’t bear to think of inline skates colliding with him on a sharp curve. I go back into the office and ask the man if he can look after these things for us; without hesitating, he opens up his van, and we shove everything inside.

My husband closes the car boot with a clunk and we glance at each other.

“Shall I drive?” I offer.

He nods. “I’ll take over when we get to Kassel.”

The city’s streets are clear for us. Nevertheless, when we pull up at a traffic light opposite a police car, and the officer casually glances over at us, I feel nauseous. When we hit the motorway, I worry that we don’t have enough petrol, even though the needle is well over the ‘F,’ and I’m driving at the speed I think will save as much fuel as possible. My bladder already feels full. We’re criminals on the run now.

I zap between radio stations until I find the club music programme. The repetitive beat is the only sound my nerves can bear. My husband stares straight ahead, his face a familiar country, now occupied and distant. The car rolls along, flat meadows and dull landscapes passing us by. Cows graze in the moonlight and an eerie castle appears, a spotlight on top of a hill. This is the German Fairy-Tale Route, with its wilful children and witches. We pass a tavern called the Three Magi, a last remnant of a bygone era stranded at the side of the motorway on a grass verge as the traffic whips relentlessly past. A few sheep graze in the meadow to one side. When we near Kassel after a couple of hours, we pull over in a deserted layby. We check no one is around and I pee quickly by a hedge. We swap seats and within a few minutes, we are back on the motorway. We are focused on our task.

My husband switches radio channels; the case of a girl who was kidnapped and held in captivity for 10 years is being picked over. I have been following the story for the past few months, horrified, transfixed. Not long ago, it had seemed the worst thing that could ever happen to a person. The girl’s mother appeared on TV and spoke haltingly about her experiences, how she showed a photograph of her daughter to anyone she met. The mother held up the dog-eared photo for the audience. I remember reading how female geese who lose a gosling run around looking for it until they die of physical exhaustion. I fall asleep to the drone of the radio.

The window is clammy with moisture, my mouth is parched. We’ve stopped. I sit up, trying to work out where we are. A roadside next to a field. My husband is sitting rigidly in the driver’s seat, an open can of Red Bull stuck in the round hole next to the gearstick. I shake it: it’s almost empty. He snaps his head towards me, looks panicky, then guilty.

“Where are we?” I ask.

“Somewhere near Magdeburg,” he says, bleary-eyed. The car clock reads 4:42. There is a lone star in the sky and it’s about to fade and burn.

We get out of the car to stretch our legs, avoid looking at the car boot. The chilliness takes my breath away. Fields stretch out in front of us, brown and furrowed, the odd stubbly crop sticking out of the earth like a finger. The hum of cars from the nearby motorway is incessant; a lone heron takes off and sails above our heads. At that moment, I notice the dead fox on the road, its tongue hanging out delicately, as if it had been caught licking food from its chops; its eyes are open, staring at the car that must have hit it—ours. It is tiny, a mere cub. The perfection of its body is uncanny, as if its cause of death were wonderment, not some injury. I look at my husband, raise my eyebrows.

“He wasn’t quick enough. I couldn’t veer out of the way. He didn’t know what hit him.”

I kneel down and inspect the boy-fox’s faultless teeth, his light rust-coloured paws and dark whiskers.

“Let’s get back in the car,” I say. First, I go around to the boot and peer in. My son is still there. We climb back in and sit. The silence weighs.

“We have to talk,” I say.

My husband slowly sticks the key into the ignition and turns it, backing out onto the main road to join the trucks on the motorway.

“Why can’t we talk?” I cast around for something, anything.

“Remember when we drove up to the Ostsee to see your parents and we showed them slides of our holiday, but forgot to take out the nude ones?”

The edges around his eyes crease. He nods very slightly.

“Or when you said ‘What are we waiting for?’ when I said I wanted four children on our first date?”

A slight smile.

I smile back.

“Or when we spent Christmas on the beach in Manuel Antonio drinking rum…”

“And the hangover you had after New Year’s Eve in San José,” he adds.

“The smell of tequila still makes my stomach turn,” I say and clutch his hand.

An hour later, we park by the iron gates of the cemetery in Berlin. An insipid light is trying to push its way through the grey cloud cover. The undertaker’s cousin is waiting for us at the bottom of the three steps that lead up to his office. His mood is muted. We hand him our son and he stands, timidly, holding the wooden box, not quite sure whether to go up the steps or stay with us awhile longer. A smell of coffee drifts out from the open door, a reassuring sign that here, at least, the world seems in order.

My husband drifts off along the cemetery path. The closeness of the car journey has confined us too long and his body now seeks space. He walks away, and I watch him disappear among the plane trees and tombstones. The dawn chorus is just starting, a heartbreaking sound. I stand awkwardly, looking at my feet in front of a man I don’t know, who is holding my son. I feel that I should say something, or that I should have at least brushed my hair.

“One thing,” I say abruptly. The man looks at me expectantly. I search frantically for something. Nothing comes to mind except the one thing that’s been bothering me since I heard the undertaker’s story.

“Your cousin’s baby that died. What colour were his eyes?”

Published October 7th, 2018

Lucy Jones, born in England, has lived in Berlin since 1998. She studied German and Film at UEA/England with W.G. Sebald and later did an MA in Applied Linguistics. She is a literary translator; writers include Silke Scheuermann, Brigitte Reimann, Annemarie Schwarzenbach and Ronald M. Schernikau. Forthcoming in 2019 is Blueprint by Theresia Enzensberger. She writes reviews of German fiction (CULTurMAG, Word Without Borders). In 2008, she founded the translators’ collective Transfiction in Berlin and hosts a reading-workshop series for Berlin-based writers, Fiction Canteen. To date, her own texts have been published by SAND journal in Berlin. Find her at https://fictioncanteen.blog/ and http://www.transfiction.eu/.

Elena Dao Jing Yu is an artist based in Joshua Tree and Los Angeles, CA. Yu’s work centers around the use of diagrammatic scores to represent physical space, memory, and movement. Her scores read as both documents of the past and instructions for future works. Yu’s Chinese-New Zealand-American mother and grandmother taught her to sew, knit, and crochet at a young age. She continues these family crafts in a practice adjacent to her practice of painting, weaving and performance. Yu received a BA in Art from University of California, Los Angeles. Follow her at @elenadaojingyu and elenadaojingyu.com.