"‘Love in Bengali Dialect’ is deeply original and moving. Through sensory detail, it brings us into the body, mind, and aching heart of its narrator, showing us how every detail of the world – the tastes of food, the textures of clothing, the bright colors of flowers – is transformed through the experience of love. This story perfectly captures the anticipation, longing, and insecurity that come in a new relationship. It's a romance and a psychological study; it's a joy to read."

—Julia Phillips, contest judge and author of Disappearing Earth

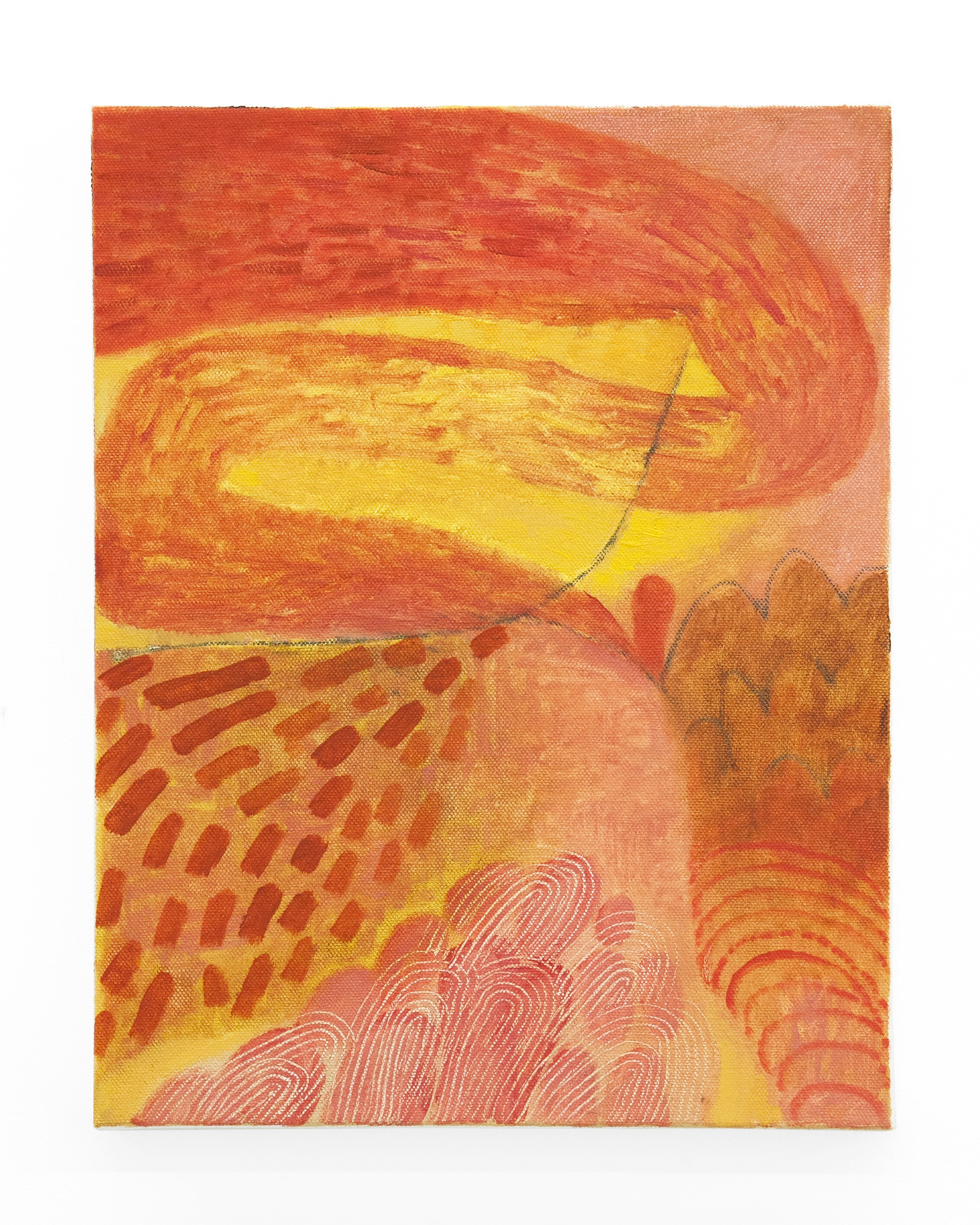

Soumya Netrabile, Garden with Blue Cloud, 2014-2015. Oil on canvas, 30 x 24 inches. Image courtesy of the artist and Pt.2 Gallery.

Love in Bengali Dialect

by Aekta Khubchandani

Winner of the 2020 Fiction Contest

Tara realizes that we can appreciate things without liking them. The pale walls of her studio apartment look like a hospital room. She is painting petals of yolk and ivory from the left corner, color in motion kissing the floor. A tea light burns, sandalwood sifting through the room. Wax candles have replaced diyas, and postcards are now pretty greetings from cities with no memories. Shudhu can’t be replaced by photographs or by the cactus he left behind, by playlists he didn’t intend to make for her. There are more flowers in mason jars and ceramic vases than hair buns and hair ties. Some people believe that indoor plants can help us with alienation. But Tara isn’t convinced by this concept.

I think at times, Tara makes chai like how Shudhu did it, but not to drink. Just to let the smell linger, as if he were still around. She hums an old song in his Bengali dialect, breaking the stillness of the room.

She has given up making wreaths for funerals in her free time and has taken up painting instead. It complements her delicate stitching style. More than that, Tara is consciously making an effort to like flowers. She often walks by Madhu Park and Khar Market to smell marigolds but returns home disappointed. Wouldn’t flowers smell the same if they didn’t wear those vibrant, bright colors? Even the lightest yellow carnation aches her eyes. She usually sticks to pastel shades and on special days she wears the dull plum T-shirt Shudhu left behind.

The studio apartment felt like home when Shudhu was around. It smelt of adrak wali chai and butter every morning. The kitchen always had a loaf of freshly baked multigrain bread, Gokul’s buffalo milk, Greek yogurt, and soaked almonds. Filter coffee accompanied idli breakfast meals twice a month. The windows opened to a sky full of birds and sun. Now there are black wires running across pillars of painted cement with parakeets parking their tails, observing the change from a distance. I don’t think the scenery has drastically changed. Maybe it’s not that the scenery for an outside observer has changed but that the way we on the inside look out at our surroundings has changed. There is a dead crow stuck upside down squeezed by the glass of a lone balcony in the adjacent building. No one lives there yet.

This could’ve been a photo essay on modern surrealism but Shudhu doesn’t live here with Tara anymore. Tara has shuffled things and doings—the chai cup he used is on the shelf, no more garlic butter on parathas, slim cheese slices instead. Clothes are ironed and then folded, not folded while ironing, fresh flowers every week in a mason jar but not too many of them and none that are yellow. The wall of frames is frameless and coated with a pasty, teal green. The mirror still has a small bindi glued to it. Tara often looks in the mirror, aligns her forehead with that bindi. She closes one eye to see how perfect it looks, between her brows.

I got Ma’s payal for her, the third time we met. I wanted to make her wear the anklet. Her feet were soft and pink, like how they would appear under clear water. I imagine her wearing a silk lehenga with the payal, like how desi actresses in films wear on their wedding nights. Tara looked perplexed at the excitement in my voice when I told her that I’d like her to meet Ma over lunch sometime. She commented on how “out of the blue” this was. All I could think was how good blue looks on her.

We’re surrounded, suffocated by the word love. Its casual overuse has polluted the essence of its emotion in an undeniable way. I want to mouth another word to describe this inexhaustible, urgent want that my heart pulsates with when she’s around. If I learned to play the harmonica, could I translate the love on my tongue to a tune for her? We can render love in many ways. Tara still wears the feather grey top that Shudhu gave her, his old checkered shirts with sneakers. I can’t deny that she looks gorgeous in those oversized clothes. She talks about the Bengali dialect, tells me how the words fill up her mouth and that she’s going to read books on Bengali literature and poetry from old writers and new. I feel jaded but when she tucks her hair behind her ear, I forget all about it. I could look at her fish eyes and the mole under her left eyelid for hours.

A crow caws. Tara peeps out of the kitchen window and goes back with a slice of bread. She’s offering crumbs to him. He looks at her; she looks at him. There’s a mutual understanding, he catches the crumb with his beak, drops it to his claws. This repeats four times. Tara could’ve hummed that old Bengali song to him. Wouldn’t this be called love? She waits patiently as he picks all the crumbs in his beak and hops to a part of the parapet neither of us can see. Love leaves. Classic love has always been gendered, measured, and depleting. Maybe this is scrumptious love or just blatant hunger.

The old architecture of bungalows and open space gardens has died at the feet of multistory buildings and basement parking; the flute walas, Shrewsbury biscuit walas, and macchi walis have changed routes. There are a few saplings in clay pots, indoor plants that sustain without the sun, lesser trees and home delivery. Pigeons and outsiders are always finding a place to stay in Bombay. We are surrounded by the death culture and a culture that’s dying. Shudhu left to be with someone else, making room for me. Tara isn’t doing well with emotional displacement. Replacement in contemporary times of Bombay is trending. Maybe it’s death’s new name. The chai Tara was making can’t be ignored anymore. She rushes to turn the gas off, takes the rag out and cleans the spill. It’s an old handkerchief with the letter “S” embroidered on it. Within seconds, before his memory dampens our afternoon, I try to invade.

“Oh ho, don’t worry. We can have chai another time. I’ve just been trying to find reasons to spend time with you.”

“Tch. Kichu nai. I’ll make another cup of chai for you.”

I smile as if to say—how can I say “no” to something (anything) you say. While sipping on tea, we talk about our favorite photograph from Pucci’s Episodes at Project 88 and the impressive group show, Modus Operandi. We talk about the texture of different words and their feelings like how wholesome the word “gum boots” sounds and pretends to be as compared to how rubbery and sweaty it can make our feet feel. We talk about negative space in art and design, and she tells me how she likes that negative space is also called breathing space in design, how humans are careless and unaware of the space they inhabit and the aura that every individual carries within themselves and how influence can adulterate it. I take measurements of her body for the turmeric bell-sleeve top I’ll be stitching for her. She’s getting her first yellow designed by me, and I think to myself how lovely that is. She’s curvier than her clothes reveal.

On long days of design discussion and project brainstorming at her studio, we’re almost always braless. We celebrate freedom of movement and comfort, exactly what we’re trying to do with our collaborative project of soft felt garments with embroidered broaches. We discuss ruffles, boat necks, buttons, noodle straps, block prints, batik, bandhani, tie and dye, malmal, cross-stitch, organic themes, transforming pastel palettes. I keep thinking about the sun melting on her skin. Her sickle-shaped eyes look tired. The mole looks like the Northern star, my fingers ache to touch. We call it a day.

Before leaving I smile foolishly at her. I tell her about how I find patterns in the way I chop mushrooms and dice capsicums while cooking. I go on about shade cards from dragon fruits, figs, goji berries, birds, and squirrels. I pause and finally tell her:

“I want to grow a plant with you.”

Soumya Netrabile, Swarm, 2018. Oil on Canvas, 9 x 14 inches. Image courtesy of the artist and Pt.2 Gallery.

We don’t forget the first person we made love to. Or who made love to us because they wanted to. The lovers, and the ones who call themselves that, transform themselves to leavers.

Tara is different. I don’t want to learn to unlove Tara. I want to inscribe a word for love, in its sacred sense, away from soiled compulsions of one body to the other.

“Ma, I’m planning to call Tara home to meet you. Breakfast sounds good, no? I’ll cook. What should we make?”

“Pankhuri, you’ve never called anyone over. Waise, when are you asking her to come over?”

“Wednesday, Ma? I was thinking of akuri or should I make omelettes with butter and jam toasts? And she likes adrak in her tea.”

“You’re sure about this? None of your friends have come home to meet me. That also, to eat with us. What is this about?”

“I’m working with her. I had told you, no? She’s nice. You’ll see,” I say, hiding my smile.

“Bas? She’s someone special, no?”

“Only a friend, Ma . . . What time should I tell her to come? Or I’ll just call her for a sleepover? I think that’ll be too fast. Nine o’clock?” I’m murmuring to myself now.

“Nine should be okay. Ask Tara. I’m going down to get milk and bread. I’m leaving the spare keys here. Kitchen drawer.”

“Accha listen. Should I wear the black and grey kurta? That jamadi linen one? We might go to the workshop later to discuss a few ideas with the karigars.”

“Haan, it looks good on you.”

It does fall well on me.

She smelled of vanilla soap and cocoa butter when she first came by the boutique. At that meeting, she tried a blouse that had to be knotted from behind. Our bodies, our energies were in unison. We were earth and soil with only the fabric between us. How do I get over that?

Tara has a concept about adapting linear shapes of origami crows and flowers to patterns on clothes. She has consciously been trying to make an effort to like flowers because he liked them for her. She has a salmon pink tiffin box full of origami memories that Shudhu gave her. It has to be him. I remember a faint reference she made while telling me about it. Her voice was gushing like river water.

There are two Taras. One, who she is now (how she is with me). And the other is what Shudhu’s love did/does to her (how she is with me when she talks about him and them and then). But there is only one me—who I am and how I want to be, effortlessly in future, around (/with) Tara. If I indulge and engage in liking Shudhu and knowing more about him, it might tell me more about Tara. But will she be closer to me or will this talking drive her toward him, he who isn’t coming back?

We are hours away from Tara coming home to meet Ma, to eat with me, us. The magazines are neatly pressed and stacked on the corner table. The rocking chair is a generation old but such a souvenir. Ma says that it adds character to our house. She’s probably right. Red and white checkered tablecloth, coasters, and a small mason jar with white daisies on the side table. I want Tara to sit on the side where the sheet of sunlight will spread smoothly across her face. The mushroom and spring onion spread is ready, the batter of eggs and milk with herbs and seasoning is waiting as well. There is sandalwood incense whirling in circles from the agarbatti I’ve just lit. Tara might like it. The maska khari from Mahim’s Bristol Bakery is an old favorite. I’ll step down and get freshly baked muffins from Bake’s House; I’m sure Ma will keep the conversation going. Does Tara dislike raisins in cake like I do? There is so much to know about one another.

This is what is going to happen. Tara will be ten to twenty minutes late. She’ll take time because she usually washes her hair on Wednesdays. She’ll tie a loose bun while traveling but she’ll open it when she’s here, when she’s home. She’ll wear Ma’s payal and it’ll feel like Sunday, like a family breakfast day. Ma will have a lot to talk about. Ma will also be thoroughly swept off her feet by my choice, pleasantly surprised. Tara will offer me help in the kitchen. We’ll have an elaborate moment of electric intimacy. She’ll feel it too. This time. From our fingers and hands touching cup plates and trays. Her left cheek dimple will be the proof. The first sign of love begins with a smile deeply felt. There’ll be cups of chai and coffee, mushrooms tucked in with cheese and milk and eggs, bread slices turned brown, glazed with butter, and jam, we’ll be the noisy bunch. We’ll talk about windows and how every room of this small house has different birds coming to visit all the time. Sparrows are fond of that room, crows and ravens like the kitchen, parakeets adore the hall when curtains are drawn and there are squirrels chasing on that double-grilled window. Then Tara will find a moment to tell me how pretty I look. She’ll say that I always manage to look that way and she wonders how, in awe. I’ll say something stupid and she’ll say, “Tch,” and a jumble of Bengali words to me out of affection (and only affection).

Before you eat, there is love. It comes even before your hunger. A writer who knows more about love than I do once wrote that. There isn’t more that I’d want for now. The undefined moment where everything is going to begin, where everything that you think may go wrong, goes wrongly right, this outpour where giving is only giving and not wanting. I’ve cooked with love. Maybe, she’ll taste the taste of it. She’ll savor it, remember it.

I send a text asking her how far away she is, whether she has gotten the right address, while humming a song with those Bengali words of hers. Will she drive down or take a cab? Will she wear a toe ring? I hope my nail paint matches her clothes, and that will be the excuse I need to take a picture of us. Will she like Ma? Will she want to come home again?

Will she wear that dull plum T-shirt?

Published July 12th, 2020

Aekta Khubchandani is a writer, and poet from Bombay. She spends her days dancing in her room and/or sitting by the window. She is currently matriculating her MFA in Creative Writing from The New School in New York. Her poems were recently awarded the winner of honorable mention by Paul Violi Prize. Her work has been featured in The Aerogram, Sky Island Journal, The Inquisitive Eater, Skylight 47, and elsewhere. Besides being published in print in national and international magazines, she has performed spoken word poetry in India, Bhutan, and New York.

Soumya Netrabile is a visual artist who moved from Mumbai to the United States when she was 7 years old. After completing her studies in engineering, Netrabile shifted focus and attended the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC), where she is still based. Netrabile is now a full time painter and ceramicist whose work has recently been exhibited by Pt.2 Gallery in Oakland and La Loma Projects in Pasadena, California.