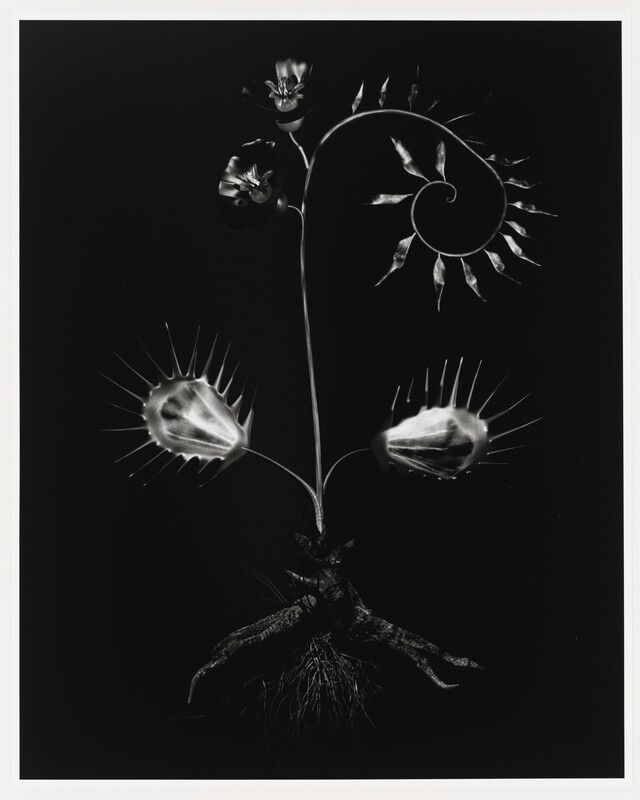

Miljohn Ruperto, Ulrik Heltoft, Voynich Botanical Studies, Voynich Botanical Studies, Specimen 56r Jaro, 2014. © Miljohn Ruperto and Ulrik Heltoft.

Letter After Leaving

by Kelsey Yoder

2019 Fiction Contest Honorable Mention

April 14, 2015

Marshall’s Tavern

100 S. Water St.

Kent, OH 44240

Dear Marshall’s Tavern,

This past weekend I visited your establishment for the first time in seven years. You still serve the same spicy tater tots with ranch, which my friend and I enjoyed early in our evening. I accept that every bartender I knew has moved on. Your liquor selection does not mirror my growth in taste, but I accept that too—nobody in this college town drinks Disaronno on the rocks. We settled on Blue Moon with a wedge of orange for nostalgia’s sake. My friend considered drinking Newcastle, but “It sits heavy,” I said to him, and we made the wise decision because when I paid our tab at the end of the night, I paid for eight beers, three for him and five for me. It’s easier, I’m sure you know, to drink five Blue Moons than five Newcastles and still catch your plane on time. He didn’t have a plane to catch, but I did.

I’m writing regarding your décor. I’m interested in a give-and-take. Hear me out: The new mural is nice—a blues-singing man with his hat dipped to cover his face—and the framed Browns jersey signed by Colt McCoy is fine too.

You see, I hadn’t seen my friend in seven years either. I’m a medical supply rep, and I get shuttled around. I told Robby I’d be in his area one night.

At my hotel, I put on an LBD with a plunging neckline. I wore heels—tough, black, with zippers and studs—because I used to be young, I used to be hip, I used to be a regular. I walked through a cloud of perfume and out the door.

Robby sat at one of your few high top tables in his faded work jeans and navy work shirt, his name embroidered in white above the left pocket. Looking at him, I felt overdressed and old, but I didn’t stop. I walked past the listing pool table, the jukebox with no songs after 1999, and the oily, yellow glow of the popcorn machine.

Which returns us to the issue: Why didn’t you leave the old restroom signs?

Men’s. Women’s. Binary aside, they hung on those doors for as long as I can remember.

Now, you have caricatures of squirrels on thin, black plastic to direct your patrons. One furry squirrel wears a top hat, his tiny, rounded ears poking out the sides. The other squirrel wears a lavender dress with a cream lace hem. Their gender-normative clothing, while restricting, isn’t the issue, but by now, you might know where I’m headed.

One night, after a graduation party, Robby and I climbed through the unlocked window of his recently vacated rental. My emerald cocktail dress snagged on the window’s latch. In my drunken impatience, I tugged and it ripped. In the living room, I forgot my dress and sat with Robby on the scratched wood floor, cross-legged, shifting to lean my back against bare walls. Our voices and the spring humidity filled the empty house. We’d been together two years then. I had graduated that week, and I was leaving the following week—“West,” I told him, “Seattle.” I was still dreaming of becoming a journalist. Robby would graduate at the end of summer and work at his family’s auto body shop. He accepted this with an ease I admired and despised.

Years later, there he was sitting across from me at your bar, holding a pint, the skin of his hand thin and tight, the fingers dark at the tips from grease. I stared at his hands as he told me about the testicular cancer that was killing him, the treatment that had failed. “How long do you have?” I asked.

“A year or two,” he said.

“How long have you known?”

“Six months,” he said and shrugged. “Today is a good day.” He lifted his beer for a cheers.

This isn’t about the squirrels, or their clothes, or the green dress I threw on top of the overflowing dumpster before leaving town.

It’s about the words.

The dapper squirrel in the top hat holds two acorns, tiny claws wrapped around the stems, and below him the word “Nuts.”

And the squirrel in the dress?

“No Nuts.” Her furry paws are empty.

Do you know how it feels to be defined by what you lack?

I know how it feels. No husband, no boyfriend, no children, no chance of progressing from sales rep to management, no home—only an apartment I sleep in ten nights a month.

Halfway through the night, I saw your new signs. In undergrad I was the girl who corrected those who spoke inappropriately. I was the girl with a minor in women’s studies. I was going places. I returned to our table and said this to be cute and charming. “Have you seen the bathroom signs?” I knew Robby had. He’d been up and down all night. I stuck my bottom lip out and threw my hands up. “No nuts!”

He saw it was a joke, my eyes asking for a little of his laughter. We had warmed to one another, but I said this and knew we had warming left to do.

Seven years ago, his laugh was a booming, maniacal thing. I’d lie face down on his bedroom carpet, and he’d lie on top of me. His broader chest pushed against my shoulder blades. I poked fun at our mutual friends, their bedroom noises, their life goals. With his lips at my ear, he’d start laughing. His laugh popped my back, the way his body quaked, his slight belly fitting in my spine’s curve. Then me on top of him, and I made him work for my laughter, made him earn the vibrations. “Your laugh is like riding waves like I’m a surfer,” he said. He’s never been surfing, and he probably never will. There’s no surf in Ohio.

I’m not a medical professional—that’s not why he told me about his cancer. I made the crack about nuts when I wanted to forget it. It wasn’t funny, but I needed his laughter, loud and forced, the end cutting into that choppy, manic chatter I love.

At closing time, we stood under buzzing streetlights waiting for our taxi. My ankles throbbed from my shoes. I had planned to cut back on drinking and smoking, but when we were outside I bummed a smoke off a fellow drunk. Robby and I passed it between splayed fingers without touching. At my hotel room, we didn’t talk. I wanted to say so much.

Miljohn Ruperto, Ulrik Heltoft, Voynich Botanical Studies, Specimen 52r Zima, 2014. © Miljohn Ruperto and Ulrik Heltoft.

The next morning, I kept my eyes closed and thought, This is the cleanest bed we’ve slept in. I thought, His body is pale in the shape of a T-shirt, the skin always covered from the sun like a father’s. I opened my eyes and he was gone. I imagined Robby walking to his truck through morning fog dense enough to wash his face, to be the cupped hands and splash of water.

I suppose that’s how out of touch I am: There’s fog here in Seattle, thick outside the window this typewriter faces. No fog where we met in Ohio. Yet I imagine the tiny particles beading on the scruff of his chin.

Go ahead. Accuse me of orchestrating a tragedy, accuse me of never appreciating you fully. You’re right. I noticed your changes, but in the dim light, I didn’t notice his.

That night after graduation, he asked me to stay. I told him to wait for me. I told him I’d return from Seattle a success. I sent him letters, called him between boyfriends, made certain he was still waiting.

He was in a band, you know. He played on your small stage. The crowd swelled and spilled their drinks. They yelled, “Play ‘Free Bird,’” and Robby yelled into the microphone, “Fuck ‘Free Bird.’” They loved him for it.

Take the squirrel signs down. Paint over the mural maroon, black—whatever it was then—dark. Burn the jersey. Put every popcorn kernel, chili flake, and shred of tater tot back on the floor. It needs to be as it was. If you do this, Robby and I will come in every night. We’ll order food and drinks and our rejuvenated metabolisms will feast without worry.

You are our bar.

I’ve moved this typewriter from apartment to apartment. Robby bought it for me, encouraging my nostalgia for a past I never had. Be a journalist, he typed on a sheet of paper. He folded it and called it a card. My typewriter is the weight of a healthy toddler, twenty-five or so pounds. If I throw it out this window into curdled fog, that’s one more empty space to define us.

Published June 23rd, 2019

Kelsey Yoder's fiction has appeared in Five Points, Midwestern Gothic, and other journals. She lives in Colorado.

Milijohn Ruperto, a Filipino, and Ulrik Heltoft, a Danish, are two artists born in the 70s who attended Yale University and who exhibited their works all over the world. In common they have a project concerning "The Voynich Manuscript", a manuscript in the Yale Beinecke Library of the XV-XVI centuries. It is a text that includes within itself a series of botanical, astronomical, astrological and biological illustrations, however, all that concerns this manuscript, where it has been written, by whom, in what language, with what purpose, is today still a mystery.