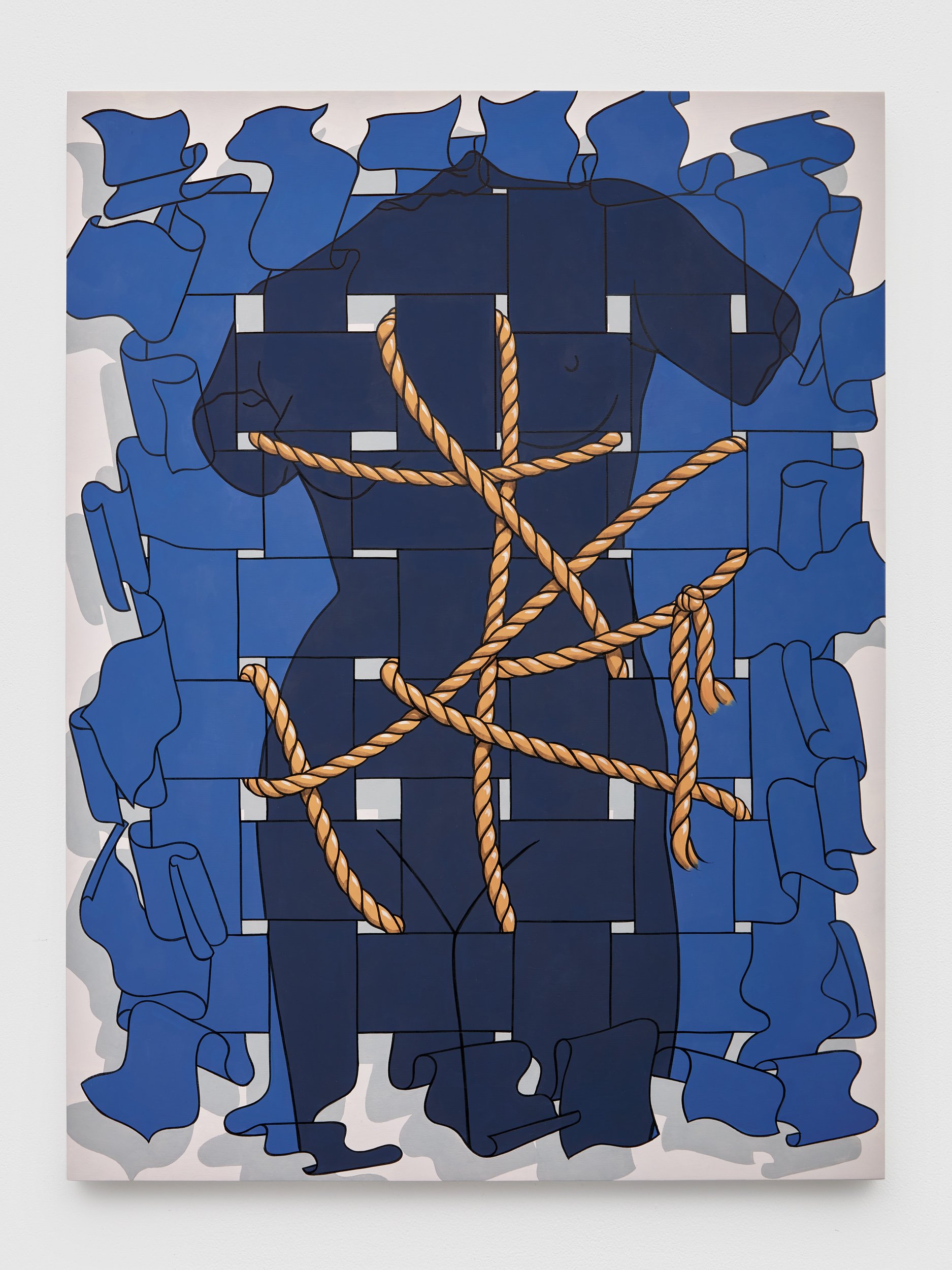

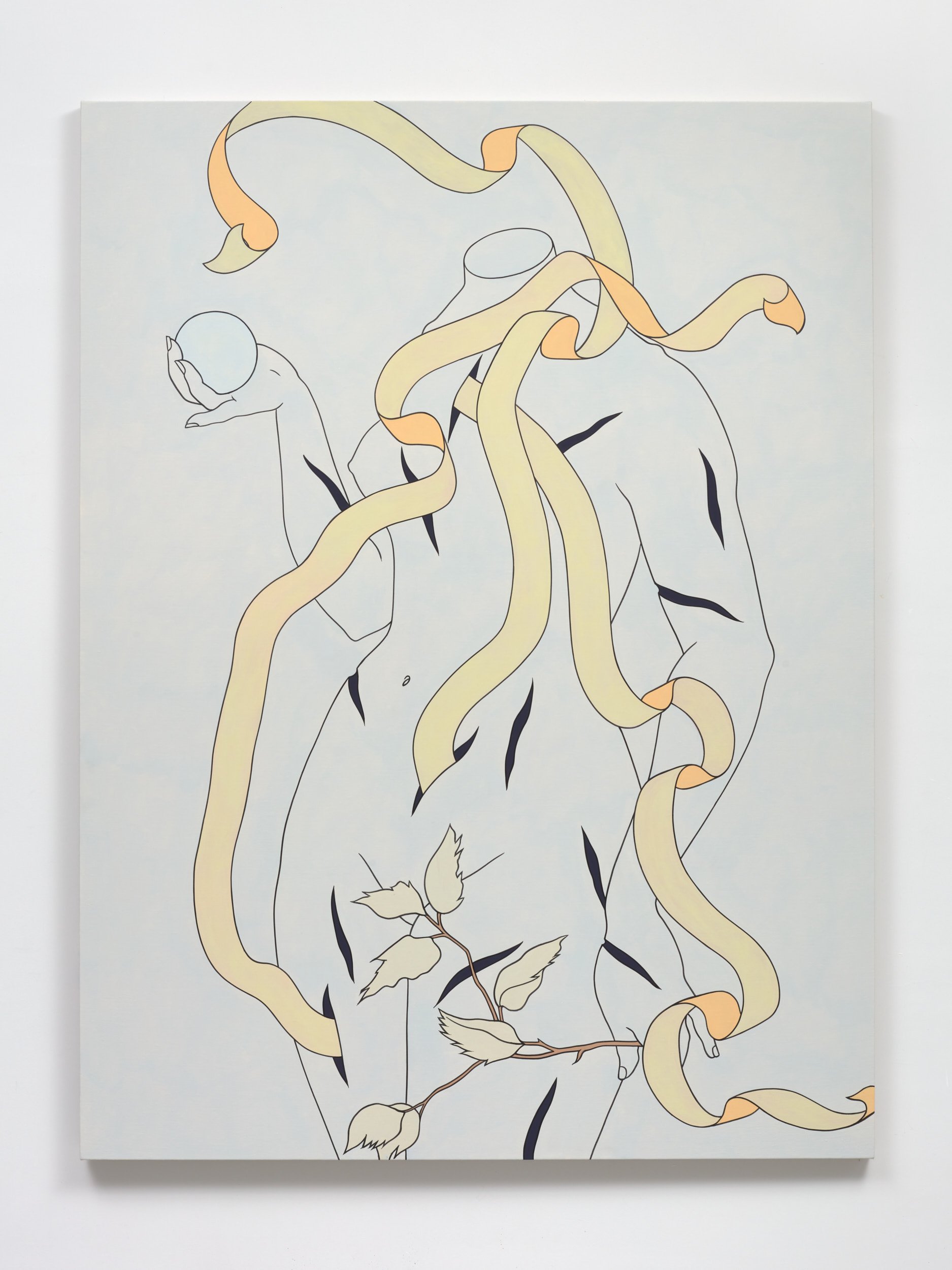

Caitlin Keogh, Spoken Drama, 2020. Acrylic on linen, 72 x 54 in. Image courtesy of the artist and Bortolami Gallery.

An Honorable Mention from our 2022 Fiction Contest,

judged by Isle McElroy

How Do You Solve a Problem Like Maria

by Eva Dunsky

“Here’s your mic,” the man says, clipping it to the back of her blouse. “You’re on in five.”

Maria goes up, does a bit about her white-passing ethnic ambiguity. She mentions Nella Larsen’s 1929 novel Passing. The set bombs. When she leaves the stage, she is smiling in defiance. What is she defying? Her own lack of aptitude? What she does know is that she’s smart. What she does believe is that she hasn’t yet found her audience.

In the parking lot outside, Maria notices Nathaniel. He tells her to call him Nate, and she calls him Natty Ice. Despite naming him for a piss-flavored beer, her first solid joke of the night, they go home together. The sex is a slab of meat being tossed on a butcher’s block. It’s the clench and unclench of her calf muscles, the grinning and bearing and waiting. Maria is twenty-one to Nathaniel’s twenty-six. Despite a conviction in all the world has to offer her, Maria doesn’t know anything other than this.

The sex gets better. They work at it until it gets better.

A year later, she is still doing sets at venues like the one where she first bombed. She’s cut Passing from her tight five at the gentle behest of her friends, though it still resonates with her in a way that feels like it should count as art.

Maria has no money but is rich in loans. She dines with friends making $60K. She goes on vacation with friends making $100K. She wonders if having money leads to better sex, if some deep sense of security underlies an ability for real release. These friends treat life as a playground, as a pleasure palace, in ways she isn’t capable of, and she blames money; she blames her upbringing. Then she goes home and smiles and talks dirty and wears lace and grins and bears it, thinking it’s what Nate wants. Nate grips the baby hairs at the base of her neck. She brings herself to come not because of him but in spite of him.

Few things make sense to Maria other than the shining dome of Nate’s head, refracting the venue’s red lighting. Her delivery is deadpan, and the audience receives her with the zoned-out silence of the very bored or very high. She keeps talking. She keeps talking until the flicker of the houselights alerts her that her time is up, then she talks even longer, until the flickering grows insistent enough to cause seizures in even the most reformed epileptic.

Nate goes from pathetic to laughable to lovable by way of sheer constancy. He is always there. Always, always there.

And it feels like she’s settling, but also like she’s lucky. Like she can convince herself of the latter. Like the former is a buoy she can hold onto in an increasingly calm sea, one that stretches toward the horizon in all directions as far as she can see.

They decide not to get married. Maria tells everyone who will listen that she’s never been one for flowers or virginal whites.

“That’s not true,” her mother says. When Maria was a little girl, she had a Polly Pocket doll. That doll had a wedding dress, a smooth white sheath of rubber that could be pulled on and off. Maria remembers it dipping generously at the bosom, showing off two hard mounds of plastic.

“Who bought the doll for me?” Maria asks. The question is rhetorical; of course it had been her mother. Nate laughs, snaking his arm around her shoulders. He loves her so much. He loves every little drop-in-the-pond detail from her childhood. Maria provides them to him sparingly.

Years pass. They cohabitate peacefully. Nate cooks, Nate cleans. Maria goes up and bombs. Still, Maria finds an agent, and Maria goes on the road. She sleeps with someone at a small college in the middle of Ohio, a grad student whose apartment smells of anemic bad breath, of a thousand exhales and no cracked windows.

Nate is angry, but they manage to work things out. Maria clings to him, aware of how much she relies on the easy comforts he provides, aware of how easily he could slip through her fingers. They argue for hours until they wear themselves out, collapsing in apologies. She runs the too-long tips of her untrimmed nails up and down Nate’s back, just the way he likes, until he falls asleep. She’s as attentive to him as she’s ever been or ever will be.

Maria spends several months avoiding the road. She stays at home and pays penance. Slowly, she weans Nate of her attention, but when it’s time to leave again, to pack her car to the roof and drive down barren highways, to alight on small, oasis-like towns full of coeds and quads so pristine they look like bad CGI, that sort of work has dried up. She does a few local gigs, but spends more and more time at home. She gets some part-time work. She tries yoga, then pilates. She starts cooking elaborate meals.

They consider themselves crusaders, living in some version of Brooklyn that’s been conjured just for them. Their streets; their shops; their dinner parties with cheap wine and hookah and the gently wagered complaints of their elderly neighbors as the hall fills with the smell of burnt spices and pot smoke. There’s something about monogamy that feels transgressive to Maria, something in the volatile instability that underlies it. She’s stable but unstable. Safe but unsafe. She could sleep with one more grad student and blow a hole in the middle of her life.

But each day cedes so gently to the next. This life that has sprouted around her treats her more kindly than she could ever treat herself.

Of course Maria gets pregnant. She’s twenty-six; it isn’t ideal, but it isn’t a tragedy.

They’ve stitched her up. Nate takes long showers while the baby nurses; she knows what he’s doing, cumming silently down the drain. He listens to a whole album as the water runs each night, The Strokes or Pavement or something in that vein, stuff with Big Nostalgic Value. She could say something onstage about the performance of orgasm, how in its natural state, an orgasm is silent and vaguely sad, a pulsing or a stuttering, depending on your parts. If she came now, would her stitches burst, blood more thin and red than clotted and menstrual? Is this comedic fodder?

Maria the Madonna of Motherhood. Smiling, serene. Raspberries blown on the bowl of her baby girl’s stomach.

Maria with warped nipples like pacifiers that have been through the dishwasher.

Maria with a single cheerio in her hair

Maria is surprised by her parenting aptitude. She enjoys it, but it catches her off guard, how she can be so naturally good at something and not have to try when there are things she’s tried so hard at that still elude her.

Nate is good at it too. Friends murmur approvingly when they see him with the baby.

“When will you start trying for another?” they ask. Not if, but when. They must assume she had been trying for the first one, or it’s a kindness they think they’re extending, insinuating (at least publicly) that the dozing infant in the stroller was an intentional choice. Maria is still young. She has time. She wants to tell her friends this, but can’t find a way to mention her relative youth without coming across as intolerable. So her friends continue to push.

How could you waste a dad who loves changing diapers? Here is another angle to take as she workshops new material to the sold-out crowds in her head, though she hasn’t found the funny part yet. Only the topic. A husband who loves changing diapers.

Maria discovers the quickest way to kick a nail-biting habit. She chews at the cuticle of her thumb, attempting to tear off a hangnail, only to taste infant shit.

Stuck at home, another joke occurs to Maria: an entire generation of women has been oversold on what the world has to offer them. Even worse, they’ve been oversold on what they have to offer the world. They’ve been oversold on their talent, on their time. These women are matriculating into adulthood now. They’re running up against the brick walls of their limitations like the protagonists of the cartoons they were raised on. Animated stars circle and buzz above their concussed heads.

Caitlin Keogh, Spoken Drama, 2020. Acrylic on linen, 72 x 54 in. Image courtesy of the artist and Bortolami Gallery.

Maria sees her life as a series of clichés, which it is, as is every life. But it’s the clichés of womanhood that bother her—the gossipy phone chatter, the burned meatloaf, a toddler’s pink sock accidentally tossed in with a load of whites.

“It’s such a cliché though, isn’t it?” Maria says. She’s on the phone with a friend she met—another cliché—in Lamaze class. They are discussing Maria’s decision to hire a babysitter for three mornings a week. The friend is telling her to hire someone ugly, so Nate won’t cheat.

Maria’s daughter attends her first day of kindergarten in a tutu and her father’s kippah. The kippah is something she found while rooting through her father’s sock drawer for some reason.

“Are you sure?” Maria asks. Her daughter may be pegged as a weirdo. Worse, she and Nate may be pegged as religious. But Maria’s daughter is insistent. She likes the kippah’s rough weave, its muted oranges and yellows. Maria drops her off early. Neither one cries as she makes her way into the school, though Maria does wonder at its size, its sprawling playground and the big double doors at its entrance. Too big for such a small child?

Maria’s daughter grows. To their delight, she is beautiful, her face a collection of arresting features that somehow fit. Maria dotes. Nate dotes. The child embarasses them with public meltdowns; she unwittingly lets on in polite company just how spoiled she is. Nate packs her lunches and Maria drives her to school. Then Maria drives home and crawls back into bed. These are the hours unaccounted for.

One day, she pulls a chilled bottle of wine from the fridge and takes a swig. The curtains are still drawn, the kitchenette dark. It’s 11 a.m. and she has no reason not to be doing this.

They won’t have any more children.

Maria’s daughter turns into a creature more beautiful than Maria, which she assumes to be the punchline of some vast cosmic joke. She’s too young to be so beautiful. For now, she is nine, and the world is a vast sea of eyes, almost none at eye level. She still holds Maria’s hand in the grocery store.

“Maybe puberty will be cruel to her,” Maria says. Nate frowns at her. He wants her to lead with compassion. He wants them to try family therapy before it’s too late and the dynamic is set.

“Do you even want to be better?” he asks. Maria tries to consider this from an intellectual standpoint, but the question isn’t intellectual. And the truth is that she does. But when she tries to explain this, it comes out garbled, and the two of them end up resolutionless, angrier for having broached the subject in the first place.

Her daughter decides to sing for her school recital. At the last minute, she pitches a fit backstage, crying and hiccuping loud enough to be heard from the audience, interrupting another child’s performance. She wants Nate to go onstage with her. He acquiesces, holding her hand as she sings something from The Sound of Music. The crowd eats it up.

Maria reluctantly records the performance on her phone. Her daughter is too old not to realize she has a middling vocal aptitude. She thinks it might be better if she were straight-up bad, rather than just okay; she pictures her washed-up, mid-twenties, trying to forge a career as a singer/songwriter with a shaky soprano and narrow range, a pitchy voice that cooperates only on good days.

Maybe they can tour together.

Is this comedic fodder?

After flowers backstage, after ice cream with friends, Maria cancels singing lessons and tells her daughter why. It can’t be taught. After tears all around, Nate begs her to reconsider, but Maria holds firm.

Instead, they buy her a tiny child-sized violin, which feels like comedic fodder. She barely practices.

On the day that Maria pays off the last of her loans, Nate toasts her with champagne at four o’clock in the afternoon. He takes a few hours off work, his phone on silent but visibly blowing up with messages he makes a show of ignoring.

The ritual feels hollow for two reasons, the first being they were paid off with Nate’s money, the second being she hasn’t yet told him about the credit card debt.

Maria develops a coping mechanism: She attends birthday parties for children at which finger sandwiches are served, cucumber and tuna for the adults and grilled cheese for the kids. She attends celebratory dinners for Nate’s colleagues who have been chosen for promotion over him; the specialty cocktails are too bubbly and too sweet, overloaded with floating fruit.

She imagines herself into a lobotomy. She makes her eyes go blank; she pictures her brain like scrambled eggs, runny with a ketchup side of hemorrhage, blood leaking slowly from her ears. She responds to her daughter with an indulgent sweetness, a vacuity, that makes her daughter nervous, even if she can’t articulate why and doesn’t want to interfere with her mother’s rare good mood. Instead of picturing herself on stage, Maria imagines herself as a vessel, a Stepford Wife who’s kept her shape well enough to still turn the occasional balding head.

Nate discovers the debt. The result is lots of crying and a marital counselor who talks incessantly about trust.

Maria starts volunteering at a charity that helps young girls find their voices, something to fill the onslaught of hours. She’s assigned as a writing coach to a student from a neighborhood she’d be reluctant to drive through, let alone visit, a fact she tries to keep from showing up on her face. She wants a role with more responsibility. She pesters the actual employees by sending copious emails and showing up at their office on her way back from the coffee shop where she meets with her mentee. They tell her there isn’t any more for her to do. The hours she’s assigned don’t justify referring to the gig as her part-time job but she does so anyway.

The young writer has talent—something unfettered about the material she turns in, unbogged by the relentless self-censoring of trying to make art as an adult.

Maria wants her daughter to come to their end-of-year reading, scheduled for a Saturday night at a venue donated by one of the most brazenly evil companies in existence. Her daughter begs off for a bat mitzvah, a choice Maria takes issue with. But her daughter is unflinching in the face of Maria’s tirade about her privilege. She doesn’t care; she won’t be swayed—as angry as she is, Maria can’t help but respect her stoicism, her unwillingness to budge. When the day arrives, her daughter climbs into the backseat of her friend’s dad’s car without a care as Maria is forced to make small talk with the man behind the wheel.

Maria ends up blowing off the reading as well. Her mentee doesn’t even like her; she won’t care if she attends. Instead she does an open mic at a coffee shop in a strip mall. She does a bit about monogamy. She does a bit about aging out of her utility to the species. She does the bit about her ethnic ambiguity.

One guy seems to appreciate it, his laugh like the quick guttural stutter of a chainsaw coming to life.

She finds him after the show.

Lets the soft, shitty animal of his body do what it wants with her own.

Maybe she’s imagining it, but it seems like the marital counselor is at a loss for words. Like she’s angry. Like she should be doing a better job of concealing her emotions. Or maybe Maria is projecting.

Published September 18th, 2022

Eva Dunsky is a writer, teacher, and translator. Her fiction and nonfiction have appeared in Joyland, The Los Angeles Review, and Cosmonauts Avenue, among others, and she’s at work on a novel. Read more of her writing at https://evaduns.ky/.

Caitlin Keogh (b. 1982 in Anchorage, Alaska) lives and works in New York. Her paintings were recently included in New Time: Art and Feminisms in the 21st Century at BAMPFA, Berkeley, CA. In 2021, Keogh completed a mural in the city of Holbaek, Denmark in conjunction with Holbaek Art. Keogh participated in Art Basel Parcours 2019, Basel, Switzerland and has been the subject of solo exhibitions at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, MA; Melas Papadopoulos, Athens, Greece; and MoMA PS1, Long Island City, NY. She has also exhibited at MoMA Warsaw, Poland; the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY; Künstlerhaus Bremen, Germany; and the Queens Museum, Queens, NY. Her work is represented in the collections of the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston, the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, and the Cornell Fine Arts Museum in Winter Park, Florida.