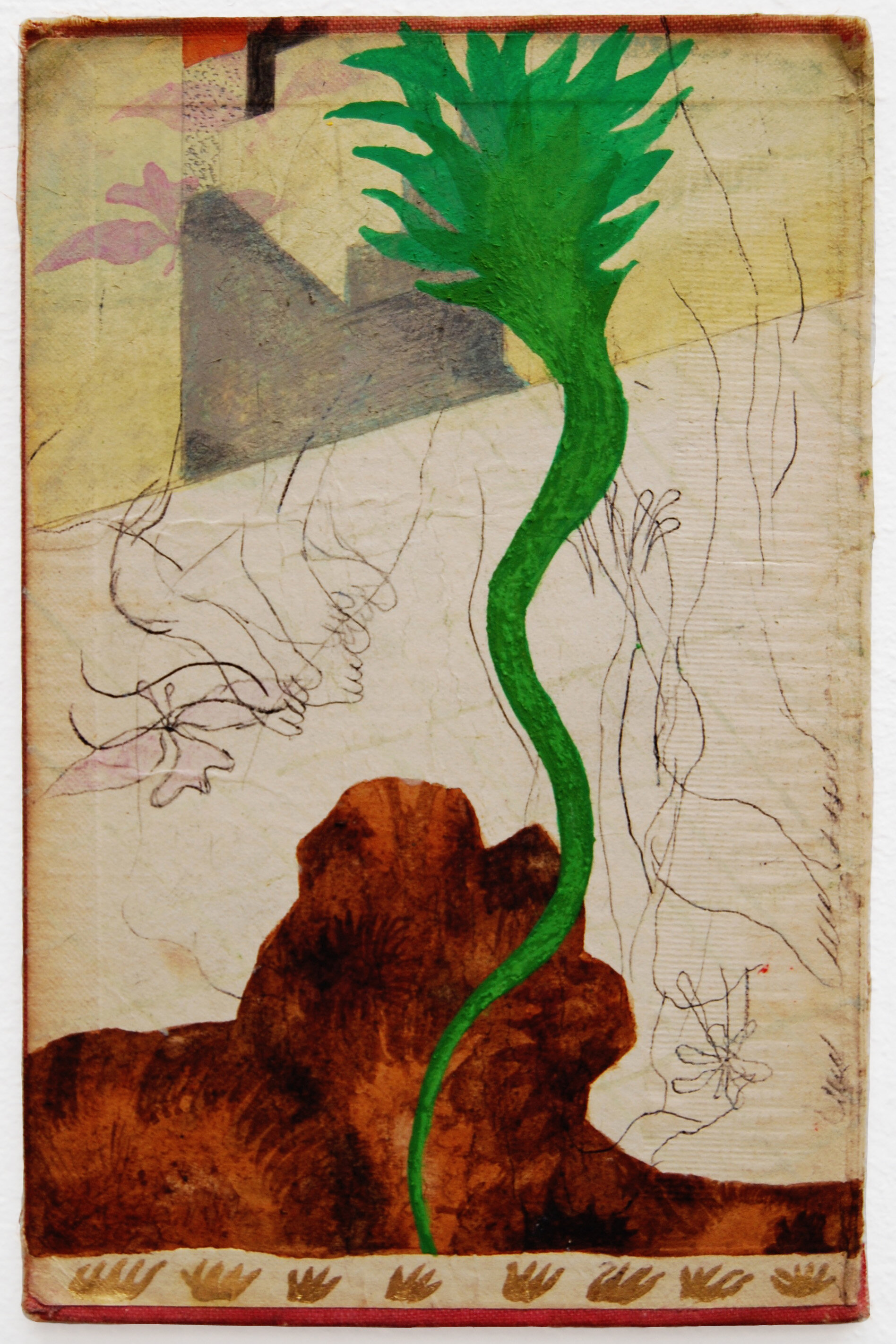

Holly Mills, Poplars have feelings too, 2020. Mixed Media on book cover, 13x18cm. Image courtesy of the artist.

Don’t Look

by Emily James

And then, that spring when the lines formed out the hospital doors, and all the masks were out of stock and the nurses cried in their Ubers on the way home to no one, we planted seeds.

We tore tape off the Amazon box and read aloud from the directions at the kitchen table: three per pod. Sunflowers, because they stretch higher than people, so we could stare up feeling small. We pressed the seeds below the dirt, brown flakes catching in our fingernails. Overplant, we thought, and decide later what to do. First, see what will grow.

Everywhere else, we see what will vanish. Yeast packets from supplier boxes, delivery pickup windows. Confidence in the eyes of doctors, our parents, people we trust. Big freezers stand empty in grocery aisles. Our children’s lunchboxes find seats in the back of top shelves, lie open, unused.

They sprouted within days, an open-seed shell curled and crooked off their unfurling leaves. Each morning we peered over the seedling trays in our pajamas, News 12 blaring behind, coffee growing cold, abandoned cereal sopping up milk.

The people died, but the seeds all grew.

We let them clutch the soil with fighting roots. We didn’t want to thin them, to take something that was budding and reaching toward the light and clip its veins.

But today is different. We sit cross-legged in the yard, a yellow bag of mulch slouched open. Twenty-four starter pods, the width of poker chips, each with long, lean sprouts.

The garden shovel looks big in my daughter’s tiny hands. We don’t wear gloves.

We fill small transplant pots with soil, dig our fingers into the dirt and let its crumbs fall on our ankles and wrists, coating ourselves in the mess we’d run from for weeks. Washing our hands, our necks, the soles of our shoes, wiping our doorknobs and our plastic packages of frozen fruit stacked in freezers. Today we can live inside this filth, the sun sinking slowly behind the tangles of our mother-daughter curls.

We don’t realize the things we’ve stopped needing. The breakfast sandwiches we exchanged cash for at the corner store, the monthly train pass our credit cards almost declined, pink gel on our fingers and salt scrub on our toes.

Holly Mills, Carefully, 2020. Mixed Media on book cover, 13x19cm. Image courtesy of the artist.

I tell her about the thinning. You have to pick one, I say. Pinch off the others. She holds the pod with three different sunflower stalks, thin as yarn.

But they’re all alive, she says.

And all of them are, when they enter the hospital doors. Some of them are my uncles, walking in, shirts tucked, deodorant rubbed beneath their arms. Lungs heavy, fluid-filled. Planning their exit as soon as they arrive.

It’s too sad, she says, Because they’re all alive. Even the ones that are kind of crooked. See?

Some of them are my father, in a grey room on a steel-wheeled bed. Clothes in a heap on the hospital chair, his Hilfiger polo from Marshalls, waiting to be put back on, or shoved in a plastic bag, tossed into a storage room and picked up by next of kin.

And then I tell her the lie I’ve tried to tell myself. We are just choosing one stem, I say, to give it more life. It will be better off without the others. To not have to fight.

She looks under the pods, the thin white wiry roots zigzagging out of the bottoms.

No, Mommy, look. They’re grown together.

Some of them are my husband, whose feet rest against my calf most nights while we sleep. Socks with a hole in the heel. Inhaler in the bedside table, open, ready to give breath. Keys that will hang by the door long after there is no place left to go.

I can’t, she says. And I understand. Neither could I until this moment, when I see her looking at me, swallowing, and I know I have to teach her a lesson I haven’t learned. That some things reaching up toward the sky—the next place, all their plans lined up on the page—are taken. There’s not enough space, help, beds. Time.

And still, when the time comes, we will race to come back. We will shove kids into buildings, so cash registers can open and close. The men who decide these things will speak to us from ventilated rooms with distance between them, their suits pressed and brown. They’ll announce and announce. Uninterrupted. They will say things like as of right now and unfortunately and we’re doing our best. The circles under their eyes turn grey, their pupils too far to see if they believe that it’s true: that Money and Money and Money will save us.

Close your eyes, I say, Don’t look. And I pinch the smaller stems, using the strength she gives me with her tiny shoulders and bare feet, those questions she asks that strum everything alive and afraid inside me. Don’t look, I say, small bits of the stem’s liquid pooled into my fingers, the life inside.

Some of them are me, a mother whose favorite shirts will be sewn into a daughter’s pillowcase as she grows without friends to lean against in class, to measure her height against on the playground.

We don’t look, as I toss them to the pavement where they lie, flat, budding leaves that learned in an instant to lie limp, to wilt under an American sun that falls, and rises, and falls again.

Published November 1st, 2020

Emily James is a teacher and writer in NYC. She is the submissions editor at Pidgeonholes and the CNF Editor at Porcupine lit. She’s a Smokelong Flash 2020 Finalist, and the winner of the 2019 Bechtel Prize. Her work can be found in Guernica, River Teeth, The Atticus Review, Jellyfish Review, and elsewhere.

Holly Mills is a London-based artist. After graduating from Camberwell College of Arts (University of the Arts London) with a BA in Illustration, Mills attended The Drawing Year at The Royal Drawing School. She has since widely exhibited her work in London, including shows at BEERS London, Lewisham Art House, Somerset House and Christie’s. Mills has also been part of shows in Bristol, Los Angeles and New York. Her most recent exhibit, Under the Hill, was with Mary Herbert at Art Hub Gallery this past March. Mills’ work is available at Wondering People.