Eileen Quinlan, Smoke & Mirrors, 2009. Chromogenic print, 20 x 24 in. Image courtesy of the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Controlled Burn

by Kate Tooley

It happened every third Wednesday and had for six years, so when the house failed to burn down on that April evening, Selma found herself at a loss. She’d set up on the back lawn with a shaker of Bombay gin martinis and a croissant she’d treated herself to, a slight improvement over her usual beer and bag of sourdough pretzels—tonight, she knew, would be special. And then the house just . . . didn’t burn.

The first time everything she owned caught fire, only a few months after she moved in, her body unfisted with fear: bladder emptying, knees buckling; getting her fingers to dial was like working a claw machine. By the time the police got there, an hour later, the house had returned to normal. No fire. No visible signs of damage at all. They nearly arrested her for making a “false 911 call,” and her neighbor suggested she check herself into the hospital for a few days, side-eying the damp patch on her jeans and the perfectly intact house. It was only later she noticed the pile of ash on her bedside table where her dog-eared book of Elizabeth Bishop poems, a birthday gift from her first girlfriend, always sat.

After that, every month like clockwork the house burned, and she never called for help. No one else seemed to be able to see or feel it, but if she didn’t get out fast enough or stood too close, the heat would burn her skin and she’d cough smoke for days. And every time, something precious to her—a blue ceramic cat gifted by her great aunt, a scarf clumsily crocheted by a long-lost friend—would be gone, a tiny pile of ash in its place.

The second time it happened, Selma caught her foot on the kitchen rug trying to escape the rushing flames, bruising her knees and searing her lungs with a too-deep, startled breath. She sat sobbing alone at the edge of the woods wishing that she’d listened to her best friend, who was a Pisces and had told her not to throw her savings into the place because you should never make big life decisions after a divorce and because besides being a “fixer-upper” and “a million miles from anything,” it had “bad energy.” She’d laughed at the time, wanted something of her own more than she’d wanted to be safe. And the house with its honest-to-god white picket fence, bay window, and rose bushes was what everyone told her happiness looked like. There was another small nondescript pile of ash that she couldn’t identify until much later: a cassette of Natalie Cole her ten-year-old self had taken from her grandmother’s bedroom while the rest of the family was downstairs at the old woman’s wake. She only listened to it on special occasions and it always made her cry.

The third time, it felt as if her body were catching fire with the house, the pain peaking and tipping over into numbness. Selma watched everything burn and observed her body’s reaction with a fascinated detachment. The kind she’d heard sometimes happens to torture victims or saints. That was the first time she began to wonder if there was a pattern to the burned items. In the back of her desk, a pile of ash replaced hidden letters from a curly-haired, soft-lipped girl she’d fallen for at fourteen; when the girl’s family moved across the country, Selma thought it was the end of the world, but it had hurt even more when the letters stopped.

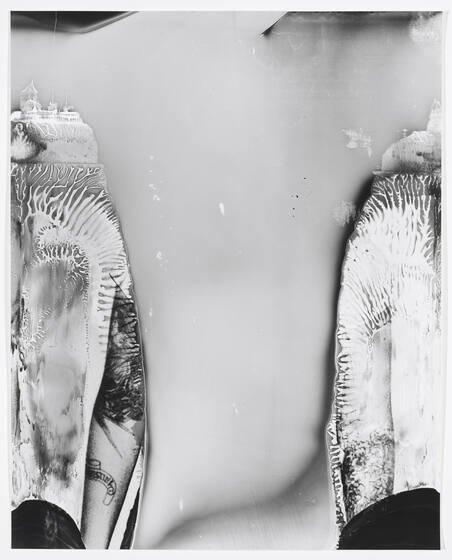

Eileen Quinlan, Failed Portrait, 2013. Gelatin silver print, 20 x 25 in. Image courtesy of the Whitney Museum of American Art.

After a while, she came to enjoy the destruction. Once she had the routine of it down, she set up a hammock at the edge of the yard where she could curl up with a drink and read her book by the light of the flames. The house was always there afterward, mostly as she’d left it: fruit on the cutting board, towel thrown over the bath railing, her betta fish Chester sulking in his rock cave, and one less piece of the past to clutter her with pain. There was a beautiful quality to cutting those ties—to becoming a creature that existed, survived only in the moment. A removal of memory and regret and loss. A decomplication of the soul.

When the summer rain sheeted down or ice crusted the knots of the hammock, she’d stay with her sister Jody in Scranton. Jody was ten years older, congenitally and happily single, and never listened to a word Selma said. Sometimes Selma wanted to tell her about the fires the way you want a cigarette after a bad day at work, but she always remembered humiliation: the discomfort twisting up her neighbors’ faces, the condescending, Sunday preacher kind of lecture from the twenty-year-old cop. Instead, she forced herself to talk about a new pair of shoes or Jody’s cat and its debilitating allergies while she wondered what part of herself wouldn’t be there in the morning.

The one and only time that Jody visited, four years after she moved in, she said, “Jesus Selma, you’ve really taken minimalism a little far. Would it kill you to have a knickknack or two, or put up a picture?” Selma shrugged looking around the half-emptied rooms. All her life she’d been acquisitive: a collector of plush bears won for her at fairgrounds, matchbooks from romantic dinners, xo-covered notes left beside the coffee machine. Her bookshelf had been full of photo albums from every important moment of her life. She hadn’t realized until she lugged box after box into the house on moving day how heavy it all was, hadn’t realized until the fires, how light she felt when they burned.

The peace of these warm summer nights had become something she craved. But it was nearly nine o’clock and the house was sitting there calmly with the lights out, snuggled into the green of the lawn and sighing with the wind or whatever old, angry houses dream about. She’d checked her watch every five minutes for the last two hours. It had never failed to catch alight by seven. There was no reason the house would stop burning just like that. Blood pulsed in her fingertips, the hollows of her palms dampening, and she started to feel her throat constrict, fingertips going panic-numb. It couldn’t stop like this without her consent, it was unfair. The house was nearly empty of everything from her old life, but not the thing she was most afraid of burning, the last thing that recalled her to pain. The backyard seemed lonely and still without the crackle of wood and sound of floors caving in. Selma realized she was pacing, felt light-headed, buzzed through with panic, and wondered when she’d gotten out of the hammock.

Selma glanced around the now-spartan living room and breathed a sigh of relief as she emptied lawn mower gas onto her wedding album and lit a match. It was the last thing of who she’d been. Back in the hammock, she sipped a lukewarm martini and imagined the photographs (the only evidence left that she’d ever worn white and trusted the future) curling and melting. She fell asleep, lulled by the now familiar quiet of loss, and the gentle crackle of burning wood.

By the time the neighbors and the fire department arrived, the house was a shell. In the hammock sat a woman, or the body of a woman, empty, as if no one had ever lived inside her.

Published October 16th, 2022

Kate Tooley is a queer writer originally from the Atlanta area, currently living in Brooklyn. She writes about the sticky corners of gender and sexuality; complicated families; and magical animals. They hold an MFA from The New School and are an Assistant Editor at Uncharted Magazine. Their writing appears in journals including Barren Magazine, Gargoyle, and Witness, has been recognized by River Styx and Retreat West contests, and nominated for Best Microfiction and Best American Essays.

Eileen Quinlan (born 1972 in Boston, Massachusetts) is a self-described still-life photographer who shoots with medium format and large format cameras. An art critic for Art in America likened her style to that of Moholy-Nagy and James Welling. Eileen Quinlan’s black-and-white photographs call attention to the material substrate of the medium; she finds rich creative possibilities in the delicate process by which an image emerges from silver salts suspended in gelatin. In an era of ubiquitous digital images, Quinlan revives the historical avant-garde’s fascination with photographic alchemy.